This review contains spoilers

Martin Scorsese has been attempting to adapt Shūsaku Endō’s novel Silence (1966) for over two decades. Though Endō’s perspective was a Catholic one, it was still a Japanese one – in a country where being Christian remains an insignificant minority (Scorsese dedicates the film to them in the closing credits). Masahiro Shinoda directed an adaptation in 1971, but Scorsese’s adaptation offers the possibility of a new perspective – rather than associate with the Japanese locals, we associate with the Portuguese Jesuit padres and the Dutch traders, attempting to spread European knowledge and the word of the gospel.

Had the film been produced in the 90s or 00s, it might have looked quite different: never having the lush, digital cinematography which jumps off the screen, or led by Daniel Day-Lewis, Benicio del Toro and Gael García Bernal, rather than the underestimated talents of Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver. Taking on other projects, Scorsese had the time to reflect, and refine the film to perfection, knowing the book inside and out, intrinsically linked to his spirituality. This isn’t just a misguided attempt by a studio to make a cheap cash-in of a popular book.

Before watching this film with my parents for my 20th birthday, I ended up in an extended discussion with my mum about colonialism and empires, and how that very ideology becomes normalised. The world is built upon the colonial brutality of Christianity, spreading the faith as European settlers into America, Australia and Africa, eradicating cultural traditions in the process, regarding other customs as those of savages. Understanding 17th century Japan might be difficult for western viewers to comprehend outside of bill wurtz’s history of japan (2016), split between local warlords under the Tokugawa shogunate, closed off from other nations outside of the Netherlands.

As wurtz summarises in relation to the emergence of Buddhism:

knock knock. get the door, it’s Religion

“please try the religion,” he said

“no,” said everybody

“try it”

“no,” said everybody again, quieter this time

Silence could have become a mere critique of imperialism, but it remains a deeply spiritual narrative. Not since The Passion of the Christ (2005) has a spiritual film this major appeared on the big screen: Silence premiered in Rome, screened in Vatican City, with Andrew Garfield’s performance of Rodrigues praised by Pope Francis.

That is not to say that spiritual films aren’t all around us. Alejandro González Iñárritu’s The Revenant (2015) was one of the most critically lauded films of last year, relying heavily on a spiritual, natural environment, whilst Mel Gibson is returning to cinema with Hacksaw Ridge (2016) alongside Garfield. As Andrew Saladino acknowledges in his video essay The Rise (or Return?) of Christian Films, spiritual films make up a large percentage of the American box office, often produced by major studios, yet are largely overlooked in box office analyses.

Scorsese has explored explicitly spiritual themes before: in The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), he embellished and humanised the life of Jesus, leading to furore from the Catholic Church; in Kundun (1997), he explored the childhood of the Dalai Lama; whilst in Living in the Material World (2011), he depicted George Harrison’s spirituality through interviews and archive footage. Yet much of Scorsese’s most ardent fans have been raised on DiCaprio snorting coke and screwing women, or DeNiro with a gun. Though one can find traces of Scorsese’s Catholic upbringing in Taxi Driver (1976) if you look for it, it never is the focus: Paul Schrader’s screenplay posits a lost man in the existentialist darkness, roaming the streets of New York, within a city of sinners.

How Silence performs at the box office depends largely on not only if Scorsese’s followers pick up on it, but also on how it is read by both faith and non-faith audiences.

Are non-faith audiences willing to devote two and a half hours to a film about Christianity in Japan?

Are faith audiences prepared for an open debate about Christianity, where the answers are not clear cut?

My mum was shocked I was even so interested in this film. When I watched Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life (2011) a few years ago, I was bored to tears at its pointless though beautiful cinematography of the world. Yet in the years since, I have felt a growing sense of agnosticism, and a greater sense of faith. Christianity has come to be known as backwards, defined by the homophobia and transphobia of the Westboro Baptist Church, or comprised entirely of Trump voters, typified as unintelligent, racist white men unable to deal with loss of industry and shifts towards diversity – yet Christianity remains a majority, in spite of shifting demographics and a modern acceptance of atheism.

If Silence is then a narrative of religion surviving through adversity, it is perhaps a reflection of faith today – as the two Christian padres in Japan attempt to survive in a world where Christianity is outlawed at the punishment of death, it becomes a private act – representing the myth that Christianity has now become a minority. Imprisoned by the Inquisitor Masashige (Issei Ogata), days stretch on as a test of faith; the icon of Mary becomes used against them, a means of apotheosising the faith. The physical task has no real meaning – yet in the symbolic, spiritual dimension, it carries enormous weight – a reverence. A simple act becomes the backbone of the film, yet this does not diminish its value.

It’s easy to draw parallels to Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ: Rodrigues undergoes his own version of Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness as his faith is tested, leading him to question whether God is really there, or if it is just silence. As he looks in a pool of water, he sees his face manifest as the face of Jesus. Scorsese does not attempt to present a physical representation of Jesus, refusing to project the face of Willem Dafoe. Rodrigues sees Jesus as he as always seen Jesus: as a painting in the Church, finding representational form within the landscape. Jesus appears as a subjective image; later, when Rodrigues hears the voice of God, this many not be His actual voice – it is how Rodrigues subjectively interprets God (and, by extension, how Scorsese interprets Him). As Rodrigues’ bedraggled brown beard grows out, and his hair goes down to his shoulders, he cannot help but be read as analogous to the humanised Jesus, with the fears and anxieties of any other man.

Though Scorsese presents a strong portrait of Japanese Christians who are committed to their faith, Scorsese still calls into question the ethics of Christianity through the criticisms raised by Masashige. Garupe (Adam Driver) witnesses his fellow Christians drown and burn, avoiding intervention until he allows himself to become a martyr for the cause. Ferreira asks Rodrigues how much longer he will allow people to be tortured by Masashige, hanging them upside down in ‘the pit’. As a Jesuit padre, Rodrigues’ faith to God rarely falters; he cannot allow himself to stop believing.

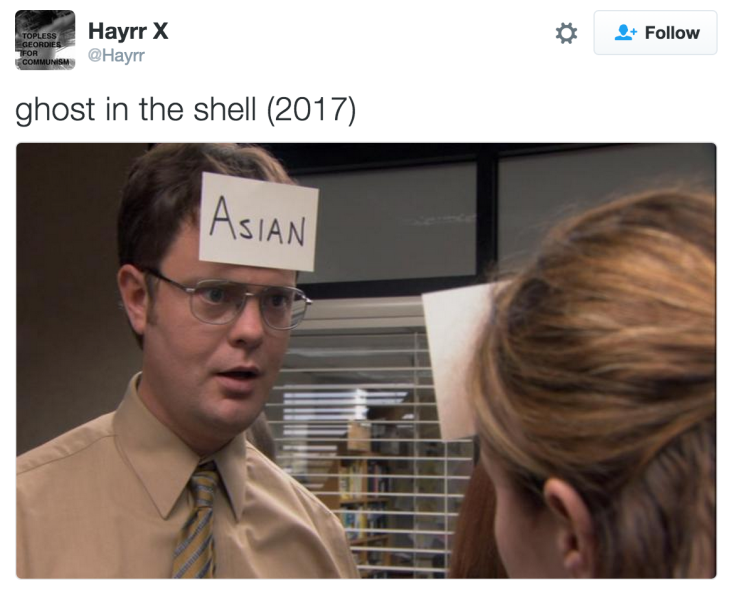

Yet the film does not centre its argument around Christianity; Scorsese devotes a significant amount of time to Buddhism, as he had done so in Kundun. Silence is perhaps the greatest examples of international filmmaking and the benefits of co-production. Shot in Taiwan, the film uses significant Japanese actors as major characters – Yôsuke Kubozuka, playing devoted peasant fisherman Kichijiro, guiding our protagonists’ illegal passage into Japan from the Chinese coast; Issei Ogata as the sympathetic Inquisitor. Had this been shot when the book was published, the filmic version could have relied on exoticised women, or yellowface villains. Asian culture has been interacting with American cinema for a long time – Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970) with Akira Kurosawa and Kinji Fukasaku, or more recent attempts to enter the Chinese market – but as Ghost in the Shell (2017)’s casting of Scarlett Johansson shows, these lessons have not been learned.

ghost in the shell (2017) pic.twitter.com/zgXyeZyK5d

— Hayrr X (@Hayrr) 7 January 2017

Scorsese never presents the film’s villains as one-sided, or place dramatic music behind them. Their methods of torture may seem excessive, crucifying followers of the faith and leaving their bodies to be battered and bruised by the sea – appropriating the cross, they become as bad as the Romans who crucified Jesus. We see heretics wrapped in straw and set on fire – yet accused witches received the same treatment across Europe around the same time, by Christians. There may be beheadings, but Christians brought the Crusades to the Middle East.

Despite Rodrigues’ dogmatic acceptance of the universal truth of Christianity, Christianity and Buddhism are not presented as absolute opposites – though they have major differences, there is connective tissue. Masashige is open to learning – he has studied the Bible, only to find it incompatible with Japanese culture. Religion is not just faith, it is a cultural system – as we see through Masashige’s approach towards monogamy and celibacy. In a world of divided politics and divided faith, Silence advocates a dialogue, outside of the binaries of black and white – Masashige treats Rodrigues as a guest, serving tea in his palace, and allowing padres to convert to Buddhism, taking on a new Japanese name, a wife, and a family.

Japan is a swamp to Christianity, where a tree’s roots has no soil to prosper in. But this is just as true today – yet Christian cultural traditions still find ways of implanting themselves, as KFC has transformed Christmas, long a secular holiday, into a national event in the Japanese market through a marketing push.

As we learn that Ferreira (Liam Neeson) has been forced to convert to Buddhism at the threat of death, we become sympathetic to his faith – he speaks of the pursuit of knowledge and astronomy, finding faith within nature and in the sun (not the son of God) – outside of the accepted knowledge of a centuries old book. Yet Ferreira and Rodrigues hold on to a silent Christianity, becoming a mythical spectacle to the Dutch traders who visit the country in the film’s conclusion. The values of Buddhism do not exempt them from their Lord. Through Neeson’s body language, mannerisms and dialogue, it becomes clear his relationship to Buddhism is conflicted. Kichijiro returns to Rodrigues, begging for confession. In the film’s revelatory final shot, we see the elderly corpse of Rodrigues, aged by the decades, moving across to reveal him holding a hidden icon of Jesus, still maintaining the faith as his body becomes enveloped in flame in cremation.

Yet Silence still remains open – it has no real answers, only silence. As Rodrigues attempts to comfort a woman before being put to death, speaking of paradiso, we become aware that these concepts are not set in stone, interpreted through human perception. Though the film attempts to communicate the message that God is always there, even in the most desperate of times, it avoids the heavy handed approach of other faith films like War Room (2015), with no grand declarations or miracles to reinforce a viewer’s faith. It remains a transformative experience – in an interview, Andrew Garfield spoke of how working on the film, preparing for over a year, has ignited his own spirituality. But it has more questions than answers, and leaves open the possibility of there being no God behind the silence for faithless audiences, letting the viewer decide.

If there is one true miracle to come from the death of Sony’s The Amazing Spider-Man (2012-14) franchise, it is this film. Andrew Garfield is worlds apart from the awkward, gawkish teenage American skater kid, communicating an authenticity and intensity that shows a devotion to the part. Garfield may have given a fair enough shot to English teenager Tommy in Never Let Me Go (2010), or to computer programmer Eduardo in The Social Network (2010) – but Silence is his defining moment, and should promise a brighter future ahead. Adam Driver’s role is minimized here, never allowing him to be as insightful or as meditative as he in Paterson (2016), yet for as much as he is in the film, he shines.

Neeson’s presence as the spiritual mentor feels almost obligatory – Jedi Master as Qui-Gon Jinn, communicating through the force; training Bruce Wayne in martial arts as Ra’s al Ghul. Silence’s narrative feels as though it could have been the story of the Star Wars prequels – Neeson as the rogue Jedi, drifted apart from the force whilst still with a connection to the light side in private, tasked to find him by two knights who still feel his presence.

Scorsese still employs some intense scenes a viewer might expect, as we see a man beheaded, his head rolling down the sand as a trail of blood is left behind him. Yet Silence never attempts to conform to the expectations a viewer might have towards Japanese cinema, never giving us samurai action nor gripping battle scenes. Silence is restrained, it is minimalistic – it is silent. Even the title sequence remains silent, placing white sans serif text against a black screen, never becoming bombastic or exciting, opening slowly to the sounds of nature. The only music within the film are hymns; even the trailer, with its rapid editing and exciting music, feels more exciting than the film itself. Scorsese could have opted for an orchestral score, but it would never lend the film the authenticity to the period it carries, and diminished its weight. Though the film’s priests never speak Spanish nor Latin, Scorsese still allows his Japanese characters to speak in their native tongue when appropriate.

Scorsese still punches the silence with narration, allowing reflectivity and mirroring the literary devices of the original novel. From the film’s brutal opening, as we see Ferreira tortured in the hot springs, to Rodrigues witnessing an execution, expressed through a subjective camera, or as Rodrigues and Garupe are spied on through the grass, Scorsese becomes reliant on long takes, playing scenes slow. Had Scorsese relied largely on dialogue, the film could have been told in ninety minutes, yet the film needs its 160 minutes to allow the viewer to meditate upon its events, and experience the film properly.

It may last three hours, yet it never becomes uninteresting; through some incredible cinematography by Rodrigo Prieto, the viewer becomes fully immersed within the film’s environment. Silence may not be for everyone, yet it is an accomplishment that Scorsese may never be able to follow up on.

You must be logged in to post a comment.