DC’s efforts to launch a cinematic universe split critical opinion, despite commercial success. Man of Steel (2013) and Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice (2016) maintained dark and gritty tones, in line with Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy (2005-12) and The Dark Knight Returns (1988). Suicide Squad (2016) balanced wide numbers of characters between an uneven structure, unable to come together. Man of Steel may be the strongest effort, reimagining Superman’s mythology, but with major flaws. Behind failures lie masterpieces: Superman: The Movie (1978), Batman (1989), Vertigo stories like V for Vendetta (2006). Introduced in Batman v Superman, attending a gala in an elaborate dress, Wonder Woman (Gal Gadot) charged into battle in the Trinity in the fight against Doomsday.

Since inception, Wonder Woman has been symbolic for young girls and women, central to protest movements, intersecting along lines of feminism. Captain America, in patriotic red white and blue, symbolises the American Dream, but often critiques it, rogue amid the corruption and conspiracy of Nixon and Reagan, or SHIELD and Tony Stark in Civil War (2006-07). Superman, lone-surviving immigrant from Krypton and young boy in rural Smallville, symbolises “truth, justice and the American way”, despite his heritage. Wonder Woman’s costume may be red, white and blue, but she’s Themysciran. Gal Gadot isn’t American either: she’s Israeli and Jewish, outspoken against the actions of Hamas, serving in the Israeli Defence Force, leading to the film’s banning in Lebanon.

The mythical Themyscira, paradise Amazonian home, plays with ancient Greek mythology: an image of waterfalls, ancient stone and luscious greens, shot in southern Italy. Young Diana (Emily Carey) grows up, introducing us to an entire culture beyond the metropolitan Gotham and Metropolis, with a unique culture with accents not out of place within the Mediterranean. However, the film never touches upon Themyscira beyond the film’s first act, leaving open questions around its inhabitants and identity following human intervention.

Diana’s origin combines multiple retellings, shaped by clay by Queen Hippolyta (Connie Nielsen), a virgin birth without father; in Blood (2011-12), Diana is revealed as Zeus’ daughter, amid confusion around her identity. Diana has an uneasy relationship with Hippolyta: Hippolyta forbids her from becoming an Amazonian warrior, trained instead by aunt Antiope (Robin Wright). Diana undergoes rites of passage of a young adult: meeting stranded American spy Steve Trevor (Chris Pine), working for British intelligence, she defies Hippolyta, taking her ship out into the human world. These conflicts aren’t uncommon: in The Contest (1994-95), dissatisfied with Diana’s inability to reshape the human world of men, Hippolyta relinquishes her title, seeking a more worthy warrior in her place. Themyscira has a conflicted relationship with our own: in Greg Rucka’s run in the mid-00s, Themyscira is a recognised nation state with an embassy in New York, Diana as ambassador, in-line with real-world geopolitics and globalisation. Diana even recently became a symbolic ambassador to the real-world UN.

Through the World War I setting, this duality rises to the fore. In the opening, Diana arrives at the Louvre, examining an image taken in the aftermath of battle in 1918 glimpsed within Batman v Superman, utilising a wartime setting similar to Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), transposing the World War II of her introduction in Sensation Comics #1 (1942) to World War I. WWI superheroes have always been retroactive, with Union Jack, introduced in The Invaders #7 (1976), deepening the legacy of Marvel’s universe. Superheroes emerged out of the vigilantes and pulp fiction of the 1930s in the shadow of the Great Depression, yet soon became a propaganda tool supporting national interests against spies, fascists and commies throughout World War II and the beginning of the Cold War.

The film adapts many elements from Marston’s first few issues, supporting characters like Steve’s secretary Etta Candy (Lucy Davis) and villains like Dr. Poison (Elena Anaya), reimagined in her Phantom-esque mask. Nazis became caricatures since WWII propaganda began, sans the uneasy politics of genocide and eugenics. In the alliance system, war is chaos. The centenary, afforded distance from living memory, allows us to reflect upon what the war represented.

Placed in the months before the signing of the armistice and Treaty of Versailles the following year, our protagonists launch into battle in the Western Front. Russia was caught in revolution; the US, having pursued an isolationist policy, joined the war, Steve smuggling information from the Ottoman Empire. The German Empire became increasingly militaristic, seen through the focus upon General Ludendorff (Danny Huston) as villain. The “war to end all wars” became a breeding ground for political ideologies as the world tried to rebuild, amid anarchy, fascism and socialism and influenza. As Rüdiger Suchsland argues in Caligari: When Horror Came to Cinema (2014), the war reshaped cinema and art, through Dadaism, expressionism, Cubism, Futurism and surrealism. Wonder Woman reminds us of the devastation: 25 million dead, mothers, children, civilians. The film’s villain is war: Wonder Woman fights against poison gas obliterating the entire world. Her fight is futile: poison gas became a powerful threat through the work of Fritz Haber, its legacy felt through the genocide of the Holocaust and use of chemical weapons within Syria.

For Jenkins, Wonder Woman is a “hero who believes in love, who is filled with love, who believes in change and the betterment of mankind”. Diana is neutral: although Germany is ostensibly the enemy, she doesn’t take sides. Wonder Woman understands both sides complexly, attempting to find resolution. Through her lasso of truth, shield and bracelets, she never uses guns, a singular force of nature storming through No Man’s Land after a year in trenches without progress. She joins forces with a multi-ethnic group of soldiers, including American Scott Trevor, Scotsman Charlie (Ewen Bremmer), fez-adorned Arab Sameer (Saïd Taghmaoui) and Native American Chief (Eugene Brave Rock). In London, we walk past multiple ethnic groups, including Sikhs. Chief embodies the responsibilities of war and its legacy, confessing to Diana that his tribe was decimated by Trevor’s people. Sameer speaks multiple tongues, including Chinese, unable to fulfil his actor dream in wartime.

We see war’s impact through everyday people: Wonder Woman protects a small German village, aghast at starvation and refugees, forced to demolish a church tower. The film implicates the culpability of man, drawing duality between the symbolic Ares and our own free will, responsible for our own destruction. Focusing upon generals, influencing without fighting war, we move beyond presidents and kings and prime ministers to individuals, their own parts to play. Does killing Ares end war? The ‘one man’ theory simplifies war: the deaths of Hussein and Bin Laden positioned as ending the war in the Middle East; Hitler as enchanting dictator, not an ideology of racism and hate. Even in Star Wars, the deaths of Vader and Palpatine didn’t stop the rise of the First Order.

Themyscira embodies duality between the classical war of myths and legends and modern warfare. In an early scene with young Diana, we move within a Renaissance-esque painting as Hippolyta relates history down through ages, telling stories of Ares. Themyscira exists outside of time; its inhabitants have no awareness the war is actually on. Steve’s crashed plane brings human war to a peaceful place. As U-boats approach the island, hidden behind an invisible barrier, Jenkins draws these parallels most clearly, dark smog dissolving into the bright blue ocean. In the direst of times, even paradise is not safe; humanity sees paradise as another place to invade. In Snyder-esque slow motion, Jenkins places us in ancient battle evoking 300 (2007), juxtaposed against modern, mechanised war. Spears slaughter modern troops; Amazonians impacted by bullets amid man’s intervention. Themyscira stands behind fraternity, honour and small, internal conflicts. Modern war, in its global powers and uncertain enemies, is outside these structures. There is no glory as a German agent refuses to face war, swallowing a cyanide capsule.

Ares acts as both symbol of war and embodied god. Never becoming the main villain, he is necessary in a mythological fight between gods, transcending human conflict behind secrecy and hidden identities in his brotherly yet torn relationship with Wonder Woman. In a CGI intensive battle, war engulfed by orange flame, the film becomes its most Snyder, interested in visual spectacle over narrative storytelling, but remains engaging. The film implies Ares’ death ends the war, celebrations in London following the armistice, but this is disingenuous. Months of fighting and real human soldiers and negotiators had to come together first.

Placing Wonder Woman as period piece may seem a distancing measure, avoiding real world politics for escapism, but superheroes always respond to the world around them. Superman, upon introduction in Action Comics #1 (1938), had been a social justice warrior, “an enforcer on behalf of the poor and disenfranchised” rallying against “social injustices” like “poverty, inadequate housing conditions, mobster violence, and corporate and political corruption.” In radio drama Clan of the Fiery Cross (1946), Superman fought the KKK, incorporating “real Klan secrets leaked by Kennedy to expose and ridicule their rituals”. Recent stories like Batman #44 (2015) engage with issues of white violence and police brutality.

Films adaptations like The Dark Knight Rises (2012) show the power of public uprising amid poverty and chaos. In Batman v Superman, the film asks theological and philosophical questions over God and the power and control of superheroes. In the Marvel Cinematic Universe, Iron Man (2008) cannot be detached from Afghanistan and the War on Terror. Wonder Woman cannot be detached from gender politics.

As Jill Lepore explores in The Secret History of Wonder Woman (2014), Wonder Woman was conceived as a “new type of woman”, who could “combat the idea that women are inferior to men, and to inspire girls to self-confidence and achievement in athletics, occupations and professions monopolized by men”. Creator William Moulton Marston had been in a polyamorous relationship with Olive Byrne and Elizabeth Holloway, attending talks by Emmeline Pankhurst and suffragist protests as a student. As Lepore argues, the World War I setting “makes a certain chronological sense”, within the Marston family’s admiration of “the formidable women who fought for suffrage, equal rights and birth control”.

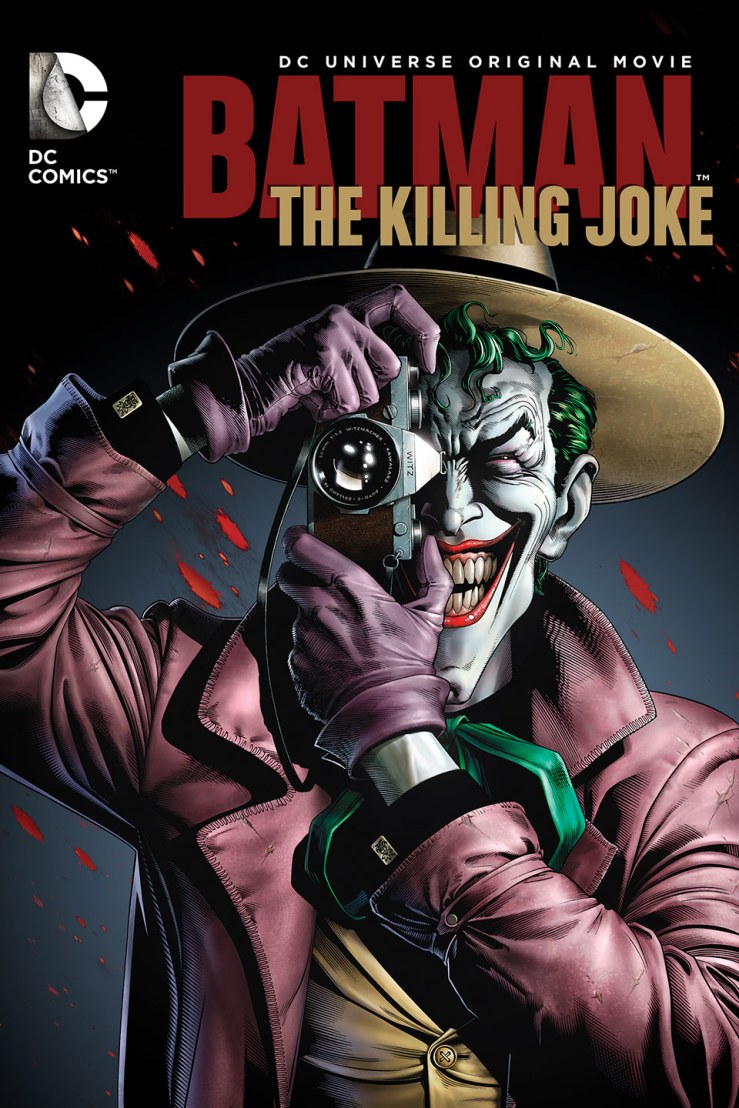

Female superhero films have largely failed, with Catwoman (2004) and Elektra (2005) unable to capture the strengths of their characters or explore issues of gender or empowerment. Supergirl (1984) might be the most enjoyable, if only because of the Christopher Reeves series and its 1980s cheesiness. But these films failed because they were bad films. Female characters are left periphery, no matter how interesting their characters are. In animated films like The Killing Joke (2016), DC struggled to present Batgirl’s sexuality in a way that isn’t deeply problematic. However, as Lepore argues, Wonder Woman is not “the Women’s March”, lacking her “American commitments and her feminist cause” as the film seeks universal audiences, positioned as “an implausible post-feminist hero”.

As Diana walks through London, a gown covering her costume, Wonder Woman is forced to dress towards conservative fashion trends, unable to carry sword or shield or expose skin. Looking through outfits in a store, she’s attracted to the most masculine and agile outfits possible to wear in battle, adopting glasses a la Diana, a nurse with her namesake in Sensation Comics #1, whose pseudonym she adopts.

This sequence resembles another in the original comic, as Wonder Woman walks down the high street, passers-by gawking at her immodesty. Were Diana walking down that same street today, she’d be fine in shorts and exposed sleeves. But wardrobe has dominated Wonder Woman’s career. In The New Wonder Woman #178-204 (1968-73), Denny O’Neil disempowered the character, placing her within the modern, groovy fashion of Swinging London.

During the 1970s, experimental artists like Dara Birnbaum, following feminist scholars like Laura Mulvey, criticised media representation of women, remixing images from The New Adventures of Wonder Woman (1975-79). More recently, questions continue to be discussed with Wonder Woman’s quickly reversed costume redesign of armour-covered skin, amid efforts for stronger female characters.

Attending a meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet, Diana faces patriarchal judgement: she cannot know secrets of war, nor act as distraction to leering, horny ministers. She explains her role to them as his secretary, christened Diana Prince by Steve, constantly told to step back and not fight, decades before women were allowed to serve. Women worked as WAACs, nurses in combat and in munitions factories, but never in front lines. Man’s instinct is to protect women, but in doing so they lose their power.

Etta Candy represents the suffragist movement, wanting to fight for women’s rights, but never too hard. Suffragist movements split between violent and non-violent action; Etta would never chain herself to a railing or set off bombs, despite her beliefs. Women marched on Washington, draped in costumes, flags and shields. In Intolerance (1916), made contemporaneously to the movement, we see early arguments around the right of children, the state and the mother, alongside lines of poverty. Etta as Steve’s secretary is ironic: Wonder Woman became relegated to the secretary for the Justice League in All-Star Comics, unable to join them on international missions. Diana believes Etta’s role amounts to slavery within man’s world, tying to the central ideology that women were “enslaved to men” without the right to vote. According to Lepore, bondage within early issues of Sensation Comics, far from kink and fetish, ties into “the iconography of suffragism, feminism and the early birth control movement”, where women marched in chains as “political theatre”.

Feminism is shifting: women in the US achieved suffrage in 1920 with the 19th amendment; women over 30 in the UK achieved it in 1918. But debates continue on, Wonder Woman hailed as feminist icon in the 1970s in Ms. magazine; the missed opportunity of Roe v Wade; third-wave feminism, between identity politics, issues of sexual abuse and inequality. Through Themyscira, Wonder Woman confronts sexuality and gender, tapping into, as Lepore argues, suffragist ideas from feminist utopian fiction that suggested “a matriarchy that predated the rise of patriarchy”, with feminist “obsession with Amazons”.

Themyscira is diverse, between black and white, but its women embody a particular kind of womanhood: largely white, cis, able-bodied, beautiful. Themyscira has no room for Asian women or trans women. The gods protect women, giving them their own island. With the arrival of Steve, Diana deals with masculinity and sexuality. Bathing in a fountain, Diana is confounded by his dick; he brags about size, whilst trying to remain respectful and apologetic to her.

On the boat, Steve doesn’t want to sleep next to her; that’s for marriage. Steve follows a set of ingrained, normative rules already feeling outdated. Diana is sex positive, reading 12 volumes on sex; she understands mechanics, but doesn’t need men. She has an island full of hot women, and her hand. Amid 1950s censorship of comic books, Sensation Comics was “accused of inciting lesbianism”. Who needs marriage? But as Steve confesses, marriages rarely stay together; men find other women. In the aftermath of battle, in snowfall, Steve talks about life in peacetime: having “breakfast”, falling in love, kids and growing old together. Immediately, they acknowledge this as bullshit, taking her up to his room and they embrace, fading to black. Sexuality isn’t linear; some cultures are free, some are more conservative.

Themyscira becomes respite from war for Steve, but he has a duty, making it out alive or not. Gadot and Pine play off each other well; Pine stretches himself beyond his role as Kirk in Star Trek (2009-present) as a dutiful man in war. However, their chemistry never feels romantic. Wonder Woman seems more interested in Sameer; her primary interest is in fighting war. In The First Avenger, we feel Steve and Peggy’s relationship more closely, understanding them as characters and what they stand for, feeling closeness and strength in their relationship. Wonder Woman attempts to manufacture connection through Steve’s watch, as symbolic memento, yet never acquires enough power.

Wonder Woman has a smaller contribution to DC’s cinematic universe than predecessors; Batman v Superman followed each origin, contained within videos on a tablet; the Flash made an unnecessary cameo fighting Boomerang In Suicide Squad. Wonder Woman has some connections, through its opening logo, Wayne Enterprises vans and an email thanking Bruce in the final scene, yet the film is largely disinterested in making Wonder Woman more than it is. Instead, Wonder Woman establishes a somewhat lighter tone, more colourful yet without sacrificing the dark and gritty elements that established this universe. In the lead-up to Snyder and Whedon’s Justice League (2017), Geoff Johns acting as executive producer, DC’s films have a way forward for an entire universe of characters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.