The BBC built a minor industry from TV movie biopics, illuminating controversial and celebrated great lives, touching upon queer figures in films like Christopher and His Kind (2011). But TV movie don’t necessarily lose ingenuity, even within limitations. Alan Clarke, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach honed their craft on TV movies, through anthology series like The Wednesday Play (1964-70) and Play for Today (1970-84), confronting social issues through humanised characters. International directors like Ingmar Bergman and Roberto Rossellini, finding their careers in decline, turned to television for funding. Even when TV movies fall into ethereality, years after broadcast, they can remain important documents of time and place, transcending limitations.

Love is the Devil was developed under relative freedom from producer George Faber, with funding from the Arts Council and Japanese and French financiers. As Maybury relates in a Q&A at the BFI, when the original cast, Malcolm McDowell and Tim Roth, backed out, he took a year to develop the script and find a story. Maybury wasn’t just approaching it as an obligatory biopic, but telling a queer perspective, having worked with queer icons like Sinead O’Connor and Boy George in music videos and studied under Derek Jarman, one of the most notable voices in underground British cinema.

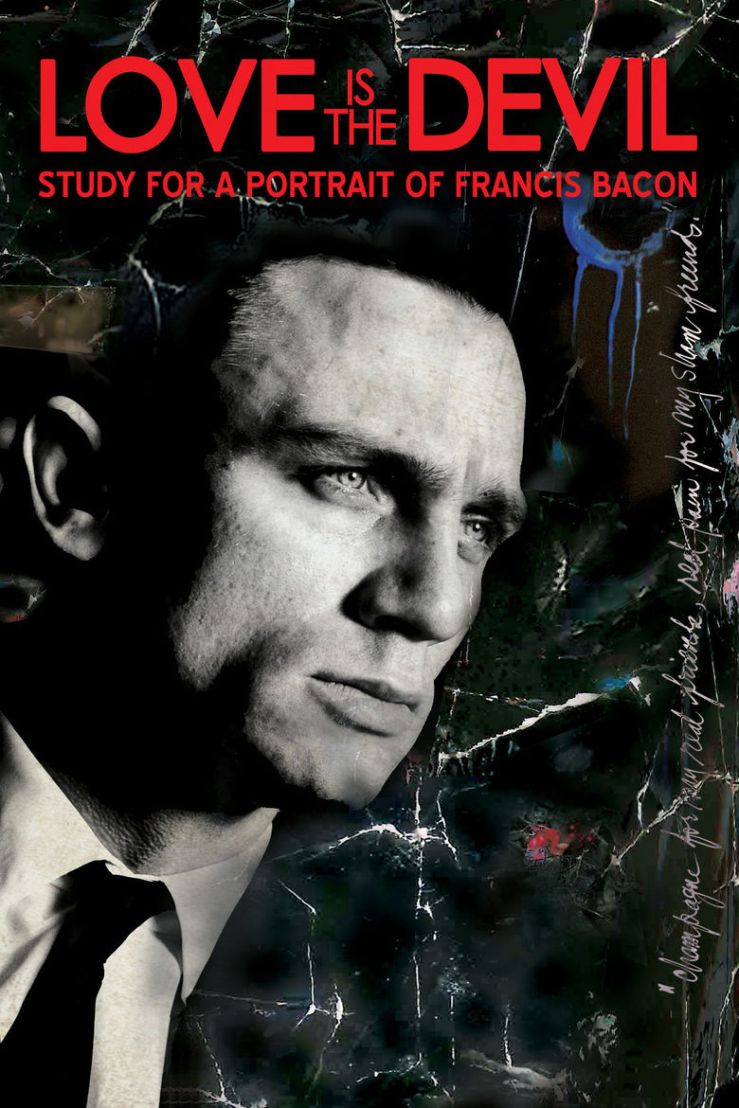

Maybury met Francis Bacon a few times before he died, but never more than briefly. As an art student, Maybury looked up to him, but Love is the Devil never glorifies its subject: it does the exact opposite, making both artist and art seem repulsive and toxic. Anyone hoping to leave the film with an appreciation for his life and work won’t find it. Bacon (Derek Jacobi) is both manipulative and self-righteous. As George Dyer (Daniel Craig) stumbles into his studio through a skylight, Bacon immediately asks Dyer to bed, without much room for an alternative answer. Without ever agreeing their relationship isn’t monogamous, Bacon leaves Dyer in the pouring rain late at night, banging on the door and screaming, as Bacon receives oral from a man he met at the local casino. He isolates himself from Dyer, framing his studio as his own space, not letting him come in with his keys.

Bacon brushes off Dyer’s suicide attempts as childish and immature, never grasping the reality, immature in himself; self-righteous to both his own and all others’ art, openly utilising Dyer as muse to fit his canvas, never appreciating the real person. In the Colony Room in Soho, he dismisses an enamoured fellow artist as a bad artist on instinct, purely from the tie he wears. Watching Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) at a local arthouse cinema with Isabel Rawsthorne (Anne Lambton), bodies and pushchairs trampled on the Odessa steps, he refuses to shut up as he intellectualises our own mortality through the death of the photographed subjects. Isabel wants to relax; he refuses the very thought. He adapts Dyer into a role he was never in, displaying covert homosexuality as he takes him to a tailor’s, trying on a suit, ties and shirts. Through his femininity, in his vain mirror routine, putting on eyelashes, powdering his face and parting his hair, he forces Dyer into feminine terms of address, using “her” pronouns and calling him his “girlfriend”. Bacon conceals an internal loneliness: he stands on the Tube, unable to think; in his studio, he can’t process Dyer’s suicide and loss.

Dyer was but one chapter of Bacon’s life; the film’s source text, The Gilded Gutter Life of Francis Bacon (1993), contained little about him. As Maybury reflects in the Q&A, Maybury’s friends interviewed for the film (many appearing as extras) had little to say, barely remembering him, leaving Craig little to go on. Instead, Maybury used poetic licence to extrapolate their relationship. Craig’s role as Dyer might seem unusual. As Bond, Craig is a ladies man; he emerges from the ocean in Casino Royale (2006), showing off his chest. Even as Jewish rebel Tuvia Bielski in Nazi-occupied Belarus in Defiance (2008), Craig cannot escape his action-oriented roles. Dyer’s entrance jumping through Bacon’s skylight might as easily be James Bond leaping across Italian rooftops in the opening to Quantum of Solace (2008).

Though lacking Bond’s musculature, Dyer still has a scruff, working class masculinity incompatible with Bacon. There’s no emotional connection; directly before his suicide in Paris, he confesses to Bacon he loves him, but Bacon refuses to reciprocate without a dismissive joke. They wander through art galleries and the British Museum, looking at other people’s paintings, but their bond never goes farther. Bacon forces Dyer into the art world he was never part of, torn from his own circle of friends, unable to transcend class differences, though still living in a grubby bathtub next to the kitchen sink. He travels across the world, attending exhibitions and openings in Paris and New York City, away from the place he calls home.

Dyer becomes Francis Bacon: in a drunken stupor, in a bar filled with sailors and Nazi costumes, he offers to spend money on other men, reutilising Bacon’s own philosophy on the image of dead people in photographs to the dismissal of others, adopting Bacon’s lack of monogamy. Dyer’s descent doesn’t feel so far apart from Franz Bieberkopf in Fox and His Friends (1975), trapped within a toxic queer relationship he stumbled into, unable to escape class. Dyer lies asleep in the casino at night, woken by a woman hoovering the floor the following morning; unable to sleep next to Bacon. Bacon pushes him into his final overdose: bottles of pills and swigs of alcohol. Maybury, living through the AIDS epidemic, drew upon his own experience. As he relates in the Q&A, he transposed his experience from the 1980s of his own boyfriend, Trojan, dying of an overdose in his London flat whilst he was away in Los Angeles shooting a music video, onto Bacon’s life, using it as a lynchpin to invest the film with currency. All around him, Maybury’s friends were dying.

Dyer’s tragedy is familiar, falling into a trope of “Bury Your Gays”. Love is the Devil is never life affirming or endearing. Biopics like I, Olga Hepnarova (2016) walk a delicate line between veracity to historical events and sensitively handling issues of mental health and sexuality. But which stories are told is a choice, for as much as authenticity wants to be held.

Love is the Devil carries visceral and intense sexuality. We see Bacon and Dyer engaged in BDSM; the camera clinically holds on the pair stripping down and taking their clothes off. In animalistic close-ups, sexuality becomes repulsive. As Maybury relates, he wanted to show the “non-beautiful side of homosexual activity”. Model Henrietta Moraes (Annabel Brooks) becomes an object for the camera. Laid bare and naked, we sense vulnerability; the photographer becomes a creep, asking her to accentuate her vagina and butt, zooming inside her, seemingly justified because Bacon lacks attraction to women.

The Colony Room becomes a meeting place for a generation of artists and painters; Maybury used local London art students as extras, whilst lacing Colony regulars with alcohol. Maybury creates a sense of the grotesque, staring through glasses and ashtrays as out-of-focuses lenses, with the same experimentalism Vertov afforded to the patrons of a Moscow bar in Man with a Movie Camera (1929). With Vertov, it felt revolutionary and a neat trick; here, it feels cheap and amateurish, attempting to apply the same techniques to narrative cinema. We stare down the faces of men and women eating live lobster, as Dyer struggles to understand the need for different sets of cutlery, though it were the scathing, bourgeois class critique of an earlier generation. Ancillary female characters in the Colony are never given their due; Muriel Belcher (Tilda Swinton) never has the presence to Swinton’s many other roles, from maternal roles in films like Thumbsucker (2005) and We Need to Talk About Kevin (2011) to the rock and roll vampire lover of Only Lovers Left Alive (2013). Swinton can fit into basically any role and make bad movies great, yet struggles to even be recognisable. International locations like New York City never feel authentic, showing the limitations of the TV movie. Dyer stands upon the roof of a hotel about to jump, as worried hotel clerk try to intervene. But the constraints of the hotel feel false, a studio set: Dyer stands in front of the American flag as identifying symbol, cars passing underneath. Actors fail to provide American accents with even a hint of realism.

Setting a film within the queer subculture of 1960s London should underline the film with political undertones. By the late 90s, queerness was still taboo: a marketing technique used by advertisers, yet Section 28 was still in effect, without an equal age of consent, a community reeling from the still very real effects of AIDS. Series like Queer as Folk (1999-2000) proved liberating and confrontational to a generation of queer (and straight) youth. Half a decade earlier, directors like Gus Van Sant and Gregg Araki opened the floodgates within American cinema through the movement dubbed New Queer Cinema. But Love is the Devil struggles to feel as revolutionary as New Queer Cinema’s strongest moments. Victim (1961), reportedly the first film to ever explicitly use the word “homosexual” on film, created a perfect sense of the isolated and underground community in 1960s London, and dangers of blackmail and law enforcement. Bacon’s flat is raided for drugs by police, Bacon displaying openness and brashness, but we never sense any ulterior motive. In the sauna, we sense an encoded queer space for sexual meeting, yet the film never makes this stated.

Perhaps the film’s most interesting aspect is it’s aesthetic. The Marlborough Gallery, on behalf of Bacon’s estate, issued injunctions against the film, disavowing the screenplay and refusing access to Bacon’s studio or use of his artwork. Maybury found this liberating: production designer Adam MacDonald made the most of limited resources, allowing them to “abandon rules of narrative cinema” in favour of the abstract, using what Maybury describes in the Q&A as “celluloid as paint”. Maybury allowed the film to have theatricality, evoking Bacon’s tableaus and triptychs, relying upon the stationary image; as he comments, “the real director of the film is Francis Bacon”.

Naked bodies bathe in blood, leaping through a swimming pool; Bacon, in his studio, turns the canvas into himself, forming internal duality between orange and blue paint. Dyer drunkenly pisses into a painting of a toilet, dripping down in yellow stains, thinking it to be real. The closest we see of Bacon’s own art is through workbooks and boxes of photographs and newspaper clippings Dyer stumbles into; Dyer’s face on his desk stares into him, a source of inspiration. Although we never learn why Bacon is considered a talented painter, we’re given a sense. Limitations of time and space transcend, moving between the interview in the TV studio and the television playing at home, words still playing over in his head. The camera looks down upon Maybury in his bedroom, trapped.

The film’s cinematography pays close attention to symbolism: Bacon sharpens his knife, looking at Dyer in the reflection behind him, as though about to stab him as a serial killer victim. He sits in the photo booth, solemn, framed by lines around him. Bacon conjures a car crash from his own words, a family laying outwards upon tarmac, blood and shards of glass around them as he admires the beauty, positioning Dyer within. Dyer’s internal struggle becomes surreal: he walks down an infinite staircase; falls into the blackness of the void, an ever-decreasing circle, until becoming nothing. The bathroom is inverted as though a stage, red pillars and black interior.

In editing, the film has the late-90s edginess of films like Trainspotting (1996), yet without the same aesthetic effect, a superfluous and out-dated trope. Composer Ryuichi Sakamoto delivers the most transcendent element in its score, embodying the film’s mixed emotions of romance, desire and internal reflections. Although more melodramatic scenes focus too heavily on the piercing screams of the synthesiser, at its best, Sakamoto reaches the beauty of his score to The Revenant (2015).

Love is the Devil has many impressive elements, but Maybury, for all his technical brilliance, struggles to create a compelling portrait of an artist, nor a beautiful queer love story or tragedy. Actors like Jacobi and Swinton are capable of far more with their less repulsive characters. Love is the Devil is of interest, but ultimately disappointing.

You must be logged in to post a comment.