Before Lumet became mainstream, he worked on the periphery of independence, with The Pawnbroker distributed through Ely Landau’s American International Pictures. As Mark Harris notes in Scenes from a Revolution (2008), the project had been developed at MGM with Arthur Hiller as director, but requirements to soften the script led Landau to finance $1.2 million out of his pocket, with the film produced on a $930,000 budget. As Leonard J. Leff highlights in his essay on The Pawnbroker, MGM wanted the film shot in London, whereas United Artists wanted the film to lose its Holocaust element (Leff 1996:3) and Paramount turned it down outright (1996:9), with directors such as Stanley Kubrick, Karel Reisz and Franco Zeffirelli also turning it down (1996:5).

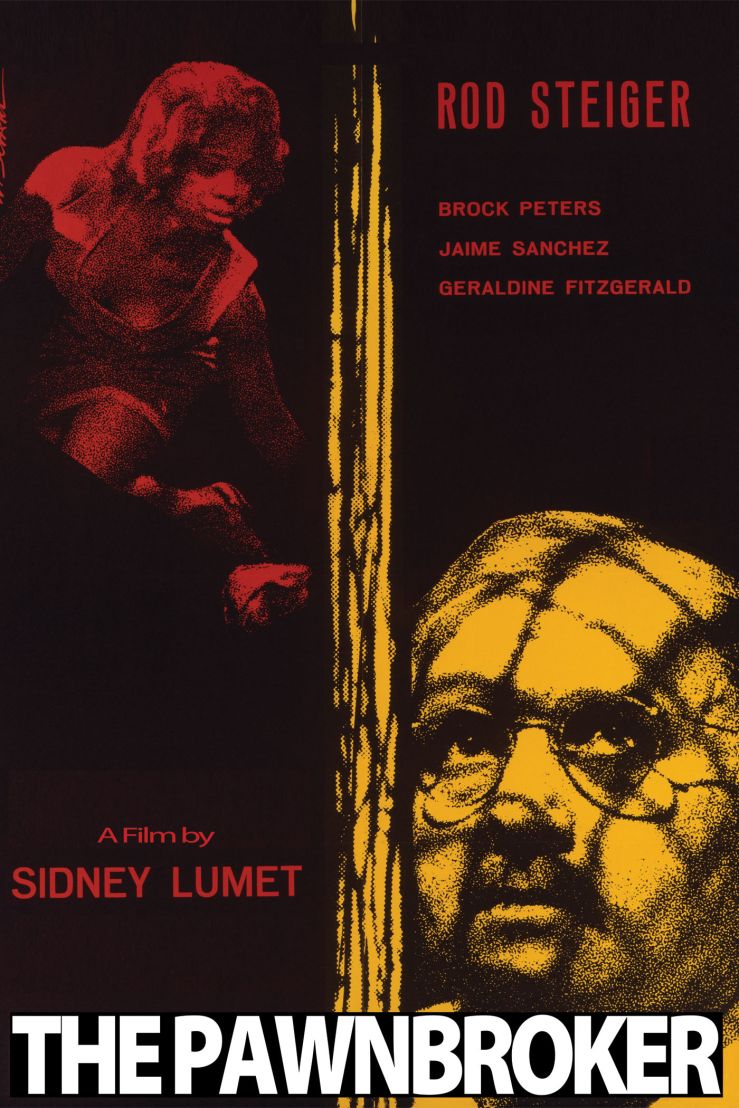

Adapted from the novel by Edward Lewis Wallant, who passed away only a year after publication, The Pawnbroker is far from a B picture, but a response to Jewish trauma of the Holocaust that should be considered in the same sentence as Lumet’s better-known works. Through its exploration of the fractured soul of Jewish, German-born (unlike the novel’s Polish Jew) New York pawnbroker and Holocaust survivor Sol Nazerman (Rod Steiger), Lumet focuses on its aftereffects. Son to Jewish immigrants, Lumet’s parents hailed from Warsaw (then a territory of the Russian Empire); Lumet’s father, Baruch, appears bedridden in the film as Tessie’s father in a powerful scene confronting the generational mortality of a people confronting genocide. Nazerman leaves him to the “land of the dead”, closing the door.

Cinematic responses to the Holocaust are complex, especially when Jewish history is the history of Hollywood, just as much as Jewish history is the history of comic books and the Frankfurt School. Hollywood studios such as Warner Bros. were founded by Jews, and this followed in Jewish directors like Nichols (nee Peschkowsky), Brooks (nee Kaminsky), Spielberg, Aronofsky and Baumbach. In part, this required an erasure of Jewish identity and nominal Anglicisation; before Hoffman’s role in The Graduate (1967), Jews weren’t considered as leading men. But beyond the liberation of concentration camps in “Pimpernel” Smith (1942), the Jewish ghetto of The Great Dictator (1940) and the largely suppressed None Shall Escape (1943), Hollywood largely ignored the Holocaust. Instead, images were left to documentarians, directors such as George Stevens working alongside the government and military. As Mark Harris masterfully portrays in Five Came Back (2014), Stevens was irreparably harmed witnessing the remnants of Dachau with his camera, capturing images of “the vastness and the specific sadism of crimes against humanity”, losing his Protestant faith and unable to confront his rushes.

The Pawnbroker’s fractured editing allows us to confront the Holocaust’s economy of images. Stevens’ depiction of liberation provided essential, indisputable visual testimony to Nuremberg. But Night Will Fall (1955) and German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (2014) would be assembled in subsequent decades; Shoah (1985) stripped away photographic evidence in favour of spoken testimony. Within other mediums, representations such as the illustrated visual testimony of Maus (1980-91), although stylised, allow us to come face to face with the Holocaust’s imagery. Directors such as Miloš Forman, Billy Wilder and Chantal Akerman would, in part, be defined within their identities as the children of survivors or victims. As Wilder recalls in Billy, How Did You Do It? (1992), he was asked by Paramount executives to change the traitor in Stalag 17 (1953) from German to Polish in order to secure German box office; Wilder instead left the studio he worked at since he fled. Kubrick abandoned The Aryan Papers after over a year’ of planning because of the weight of historical testimony; The Day the Clown Cried (1972) was suppressed through Jerry Lewis’ insistence. Produced in the immediate decades following the Holocaust, The Pawnbroker sits alongside films that alluded to the camps but rarely entered them, such as The Diary of Anne Frank (1959), Judgment at Nuremberg (1961) and The Producers (1967).

In the implacable opening we witness Nazerman’s children running through pastoral fields. In the present, Nazerman lays on a deckchair in a suburban American world of lemonade, pop music and style against rows of identical houses. We feel Nazerman’s internality: Bertha remembers the 25 years since the death of his wife Ruth, but asks Sol whether he’d like to go on a tour of Europe and feel the atmosphere of old cities. Sol’s experience is different: for him, Europe is a “graveyard” of the dead, occupied territories that marched its people to death. In the pawnshop, Nazerman’s relationship with Puerto Rican shop assistant Jesus Ortiz (Jaime Sánchez) introduces a tragedy to someone who never lived it: Ortiz notices the number imprinted on his arm, asking whether he is a member of a secret society. To survive, as Nazerman comments, he must achieve the miraculous, and “learn to walk on water”. Threatened by racketeer Rodriguez (Brock Peters), we sense Nazerman’s desire for death that will come “when you wish it hadn’t”. Merely for being a Jew born in Germany, Nazerman’s existence and autonomy has been in jeopardy since birth.

Though Lumet’s preference had been James Mason, Rod Steiger had appeared ahead of Boris Kaufman’s lens before in On the Waterfront (1954); Steiger had been attached since early on and contributed to the screenplay (Leff 1996:5). In The Pawnbroker, Steiger portrays the difficulties of suffering from PTSD, constructing a cage within and burying trauma. Nazerman walks through East Harlem as nobody, his pawnshop one among many others. On the subway, he moves between cars, focusing intently on gazes: what’s on other minds, what he represents through mere appearance. This constant motion is something we see again in Son of Saul (2015): the camera follows Saul from behind across the chambers and camp, the frame’s corners forcing us to bear witness to his complicity and the loss of the body’s sanctity Saul is forced to ignore. The complexity of memory becomes dislocated in another city, country and time. Though his relationship with Ortiz carries a trace of his life as a professor, it can never be identical.

Nazerman suffers survivor’s guilt: why did he live, and not the family and friends around him? As he reflects to social worker Marilyn Birchfield (Geraldine Fitzgerald):

I didn’t die. Everything that I loved was taken away from me, and I did not die.

Initially, Marilyn sees his surface, asking whether “blood really flow[s] through you”. As he tells her, he has escaped from emotions, without desire for vengeance. Nazerman walks through dark corridors to find her Long Island apartment, desiring companionship. Looking from her balcony at the city’s outskirts, he comes to understand the memories flooding his mind. In the front room, Lumet portrays stillness: Marilyn tries to take in the immensity, but cannot. Just as Nazerman is powerless, so too are viewers, unable to change history.

The Pawnbroker’s New York setting is fitting, especially considering the Jewish communities depicted in films like Hester Street (1975) that explored the cultural practices within the 1890s wave of Russian Jewish immigration and assimilation Lumet’s father was a part of. But The Pawnbroker’s East Harlem setting is also fitting to Lumet’s wider canon: the New York talent of theatre and television, the cross-section of jurors in 12 Angry Men (1957), the apartments of The Anderson Tapes (1971), the police corruption and racial profiling within Italian American communities of the Bronx of Serpico (1973), and the Brooklyn bank heist of Dog Day Afternoon (1975). Although Lumet worked with Connery and British settings throughout the 60s and 70s, New York City’s geography remains essential. We hear auditory landscapes, subway cars rattling, in a city dotted with Pepsi logos, Loew’s Theatre and night-lights. Nazerman’s Jewish identity coexists alongside the city’s diversity, an immediate affront to Nazi racial genocide, and indeed must coexist along the intersections of American, German and New Yorker. From Irish to Italian immigrants, American race is but a construct, responding to contradictions of ethnicity, politicisation, scapegoats, socialisation, the concept of the “other” and dominant power structures.

Ethnicity is a frequent factor for Lumet, even when it isn’t the focus, such as in the racial assumptions of 12 Angry Men, and the West Indies-born Jacko in The Hill (1965), suffering endemic racial discrimination despite himself being a member of the Commonwealth. In The Pawnbroker, Lumet embraces the youthful sexuality of Ortiz and his black girlfriend, framing close-up kissing faces and their laughter in sexual embrace. Black onlookers witness chaos unfolding from windows above as Ortiz crawls onto the sidewalk with documentary realism. Composer Quincy Jones places himself alongside black film and the black music industry, working with Steiger and Poitier on In the Heat of the Night, defining a generation with Fresh Prince and meeting and working with figures that include Mandela, Malcolm X, Cosby, Tupac, Prince and Stevie Wonder. However, Jones faced systematic racial discrimination from Hollywood. As he recalls of In Cold Blood (1967):

Truman Capote, that motherfucker, he called Richard Brooks up on In Cold Blood and said, ‘Richard, I don’t understand why you’ve got a Negro doing the music for a film with no people of color in it.’ And Richard Brooks said, ‘Fuck you, he’s doing the music.’

The pawnshop carries symbolic weight: the Holocaust in part began through assaults on Jewish businesses. Kristallnacht saw Jewish property and possessions confiscated, funding the Nazi economy. Some of the Holocaust’s defining images are lost possessions: piles of shoes and glasses, reflecting lives and stories. The pawnshop, despite the racketeering deception against Nazerman, facilitates exchange. Competing forces create complicity towards anti-Semitism: the Polish Jewish identities of Kaufman and Lumet and the Russian pogroms that led immigration; American refusal to admit Jewish refugees before and during World War II, and an intellectual, literary and political sphere that supported eugenics. In film, Lois Weber’s abortion narrative Where Are My Children? (1916) depicted eugenics as a viable option to abolishing poverty, disability and the lower classes. The Holocaust had been orchestrated through policies and infrastructure marginalising and attacking minorities and the disabled, and the complicity (in structures and individuals) of occupied territories. Even in the land of freedom, a nation founded on the genocide of Native Americans, Nazerman cannot escape anti-Semitism. As Bernard Perlin juxtaposes in his painting Orthodox Boys (1948), Jewish street subjects stand alongside a wall of graffiti, including the swastika. Spiritually, economically, temporally, and in the days of the working week, everything has a cost. But Nazerman is a victim of the costs of war: he doesn’t owe anyone anything.

Nazerman’s values have lost meaning against the cost of 6 million lives. Toward every customer and barterer, Nazerman manipulates an item’s cost, slashed or inflated: a gold award, sold for a dollar; a locket with no fixable price; a Laika camera, shifting between $20, $50, $2 and the $12.50 sign. Between profit and loss, Nazerman doesn’t care about bosses. As we hear a radio’s distorted tones, overwhelming Nazerman, we realise an object’s multiple values: a woman pawning her mother’s radio; Nazerman living in a state that solidified the dissemination of propaganda through mass-produced radios (Volksempfänger). Marilyn initially visits as a “new neighbor” asking for a sponsor and coach to invest in children’s sports. An elderly black customer visits in loneliness, “hungry for talk” and discussing philosophy as Nazerman sips his drink, until he leaves. Nazerman’s philosophy envisions money as the “whole thing”, life’s sole purpose and absolute beyond the speed of light. Nazerman is nihilistic: God, art, science, newspapers, politics and philosophy hold no meaning; only the constructed meaning of numbers and currency signify anything. As he closes the shop each day, he walks solemnly in darkness. In the cramped apartment, lined by a menorah, Nazerman remains contained within windows, behind curtains. As her father dies, Nazerman’s response to Tessie’s phone call lacks empathy and humanity, but instead immediately moves on: all there is to be done is to “bury him”, refusing to “come over and cry”. But the conclusion suggests Nazerman regaining emotion: Ortiz is reduced to a corpse, carried away underneath a cloak. Nazerman screams out, internal pain manifesting externally: hands bloodied, a personal relationship affecting his sense of self. Nazerman looks to the heavens towards mercy that can never come.

The dehumanisation of anti-Semitism existed long before Nazism, in notions of the Messiah, crucifixion, God and cultural traditions linked to Abrahamic faith. Nazerman relates to Ortiz “the secret of our success” before the establishment of Israel: nothing to sustain the Jewish people for “several thousand years” but a “great bearded legend”, without food, land or army, but a “mercantile heritage” of merchants, usurers, witches, pawnbrokers, sheenies, makies and kikes. As he explains:

With this little brain you go out and you buy a piece of cloth and you cut that cloth in two and you go and sell it for a penny more than you paid for it. Then you run right out and buy another piece of cloth, cut it into three pieces and sell it for three pennies profit.

Under the Nazi regime, the parasitic, conspiratorial discourse of films like Der ewige Jude (1940) contributed towards vitriolic views. As David Welch notes in Propaganda and the German Cinema 1933-1945 (2001), Jud Süss (1940) recruited Jews from the Lublin ghetto for its production (2001:240), and, according to an SS report, prompted anti-Semitic demonstrations in Berlin (2001:245). Discrimination against Nazerman becomes self-hatred: Nazerman rejects everyone, “black, white, yellow”, as scum. Nazerman has lost hope in God; Ortiz, with a cross around his neck and in his bedroom, holds on. Faith no longer unifies: St Mary’s is squeezed between a congested New York street, parishioners worshipping shrines. Marilyn might be in search for an answer, but Nazerman is still searching.

The Pawnbroker is made through Ralph Rosenblum’s revolutionary, novelistic editing, drawing parallels across temporalities. Flash cuts resemble memory beyond scripted scenes, stopping us in our tracks and interrupting our sense of the present, moving inside Kaufman’s central, indelible monochrome images. Nazerman’s nightmares unveil in progression: one image is revealed, before an associated image is recalled as the scene becomes more structured. Memory is constant: remembering, re-evaluating, recontextualising, reforming. Time distorts memory, collapsing images and events into one whole, repressing and writing over others. Nazerman seeks to be frozen in time, in a body that should never have survived: he refuses to change the day upon the pawnshop’s calendar, before he is forced to confront a page ripped away. The Holocaust is temporal, defined by its place in time and the time afterwards. In Come and See (1985), depicting the genocide of Byelorussian villagers during the Nazi occupation, we are confronted with manipulating the immensity of time, with the boy Florya shooting his gun at a framed image of Hitler, unspooling the occupation, his rallies and his birth in reverse sequence.

Rosenblum utilises time as associations. In the opening, we witness the idyllic countryside, against blades of wheat and grass. In slow motion, children run, suspended from time, Kaufman focusing intently upon hands and smiling faces. We return throughout, depicting prosperity in peace. Later, towards the conclusion, we experience a slow dissolve from butterflies, returning to a hand in the field. In the first implementation of flash cuts, we follow Nazerman through the streets as he witnesses a gang beating up a black man, framed from a distance through the urban, steel fence. Nazerman sees, but never interacts; walking forward, the past behind him. Parallels are formed not only visually, but audibly: a dog barking, running ahead of an officer towards the camera. The camp’s barbed wire fences are more threatening than its urban counterpart, but enclose body and soul across different time periods. In the camps, Lumet disorients through attention to detail: prisoners and commandants don’t speak English, but German, but these memories are largely intended as visual spaces. Returning to the present, Nazerman begins to drive, almost mowing down a pedestrian that heckles him from behind the glass, denigrating him a nut, a moron, a bad driver: phrases and terminology that have roots in the stigmatisation of disability and the culture of eugenics.

Rosenblum achieves similar disorientation within the subway car and deportation train, unifying these spaces. Nazerman is impacted to his very soul by the subway train: his eyes dart across, a spectacle to other commuters and passengers; he shakes with anxiety across the carriage, needing to get off but unable to. By depicting the immensity of discomfort through editing and cinematography, Rosenblum parallels the rattling, blackness and lack of light by repeatedly cutting against the deportation train. We see the shaking and dishevelment of death itself, creating a sense of the stench and the smell: ashen faces, bodily fluids, a lack of life. As a baby falls to the ground, Rosenblum’s parallels the scream of the baby falling to the ground as a transition into the primal scream of Nazerman as he frees himself away from the train, his hands covering his ears and face. Rosenblum immense power of images places the viewer in a constant state of pain, never allowing us to return to our own sense of safety, The film draws other associations: a pregnant woman pawns her diamond engagement ring in desperation, only to be shocked as she learns from Nazerman that it is glass. As the camera focuses intently on his face, Rosenblum draws a parallel to the loss of possessions and bodies stolen by the Nazis: in a close-up, we witness hands upon barbed wire, and possessions removed from prisoners’ hands. As Nazerman is forced to confront his own memory, he sees his head smashed through glass by SS officers. The use of glass (and the glass of the camera lens itself), forces us to lay witness to the literal shattering of Germany’s Jewish community through the attacks on synagogues, shops and homes in the Night of Broken Glass. In Auschwitz, we witness lines and lines of new arrivals arriving at their deaths. As pressure is applied to Nazerman’s hand by Rodriguez, we flash between faces from earlier in the film in rapid succession.

Nazerman’s trauma as handled through Rosenblum’s editing addresses a real phenomenon. As Jewish writer Gila Lyons describes, trauma from the Holocaust is often epigenetic and inheritable, creating stress and anxiety, with Lyons vividly experiencing “the crunch of heavy boots on sticks and leaves” and “lines of emaciated prisoners” as she visited sleepover camp, with everyday situations triggering unshakeable associations. Lumet provides the opposite of the verisimilitude of later films like The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas (2008), that opt instead to depict the camps with an immersive attention to detail, following our protagonists into the gas chambers: witnessing uniforms, showers, and the release of poison gas, and yet perhaps achieves a more poignant effect.

Perhaps one of the most notable aspects of the film is its depiction of nudity, sexuality and the human body. Lumet was placed within a battle with both the Catholic Legion of Decency (‘Condemned’) and the Production Code, exhibiting the weakness of the 30 year old code’s longevity. But Lumet’s use of nudity is, in principle, nothing scandalous. Instead, nudity reveals both the interior of Nazerman’s character, and the true horror of the Holocaust: millions of lives stripped away from their bodies to ash. In the camps, the naked body is de-eroticised: not sexual, but human. Women are constantly threatened by the sexual violence of officers, standing over women, using them as objects to rape and abuse, disempowered and without agency but reduced to statues. In the cattle car, Nazerman not only loses his children, but his wife, as a fatal victim to the rape of officer. And yet, these situations that lack any sexuality are presented as such, through the wave of 1970s Nazisploitation of the power play of The Night Porter (1974) and films like Ilsa, She-Wolf of the SS (1975) and SS Experiment Love Camp (1976). In Bent (1997), the film’s exploration of homosexuality forces us to bear witness to an act of mutual masturbation between two male prisoners in their last days.

Nazerman is presented with the offer of a girl (Krishna Kaur Khalsa) who flashes her breasts to Nazerman, contrasted in shock cuts to the abuse of Nazerman’s wife. She describes herself as “real good”, wanting to sell her body for $20 to a pawnbroker. Though her offer is sexual, neither the situation nor Nazerman’s backstory are: Nazerman is disinterested in sexuality, his objects of affection long since dead. Nazerman places her coat over her, unable to bear the image of her naked breasts. As Mark Harris documents in Scenes from a Revolution, the film was rejected by every studio because of this scene, with Lumet refusing to provide a “protection shot”; Lumet appealed the rejection of the film and exempted the film from the Code as “a special and unique case”, creating what Harris describes as an “untenable loophole”. However, for Lyons, the “Jewish body is a vulnerable body”, a faith defined by the senses and bodily experience.

By reflecting the bars of the pawnshop upon Nazerman’s face, cinematographer Boris Kaufman (reinforcing his legacy beyond his siblings, Dziga Vertov and Mikhail Kaufman) communicates the continuation of Nazerman’s imprisonment: although Nazerman is no longer consigned to state institutionalised death, he remains imprisoned, within the walls of the pawnshops and the limitations of his self, mind and body. Burnett Guffey had achieved the masterful visual image of confinement and entrapment of the repetition of shadows of lines against the face and body in Birdman of Alcatraz (1962), but The Pawnbroker extends this imagery outside of the prison but into other spaces.

The Holocaust is not an inactive past relegated to history, but it remains living memory, even as the volume of testimony amounts to more than can be consumed within one lifetime. Poland’s recent introduction of a Holocaust law, although with a partial U-turn, emphasises how these events continue to be politicised and their perceptions are in flux, with theories of Holocaust denial continuing to be peddled online, in print and within politicians. Anti-Semitism continues to be active, both in memes and imagery and in shocking attacks and murders like the death of Holocaust survivor Mireille Knoll back in March. Genocide is not historical, but contemporary, from the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge in the 1970s, the Rwandan Genocide in the 1990s, and the genocide of the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar today by the country’s Buddhist majority. Across the Gaza Strip, in particular towards the Jewish faith, the settlement between Israelis and Palestinians has been met by decades of conflict and death.

Back in 2012, with a school party, I walked upon the stones and soil of Auschwitz Birkenau that millions were murdered upon; where millions, if not billions, have visited in the decades since. Back then, I lit a memorial candle but I did not cry. In 2014 and 2017, I visited the house the Frank family hid within in Amsterdam. But today, my sorrow would be too great to contain at the inhumanity.

You must be logged in to post a comment.