On a Sunday afternoon in early December, I had the pleasure of attending a screening of Pandora’s Box at the Phoenix Cinema (not to be confused with Leicester’s Phoenix), with a live piano score by Stephen Horne. Alongside fellow silent film enthusiast and Conrad Veidt lover Max, Max had attended their showing of Häxan (1922) a month earlier, with live narration by Reece Shearsmith. As we took the train down amid the chaos of cancellations, we sat down to an ornately decorated screen, as though in the pre-digital age of decades ago, before physical film projection was usurped by bootleg VHS tapes, torrents, DVDs and streaming, the pillarbox screen the centre of attention amid the wooden seats. Critic Pamela Hutchinson provided a brief introduction to coincide with her BFI Film Classics monograph, outlining some of the initial negative critical responses.

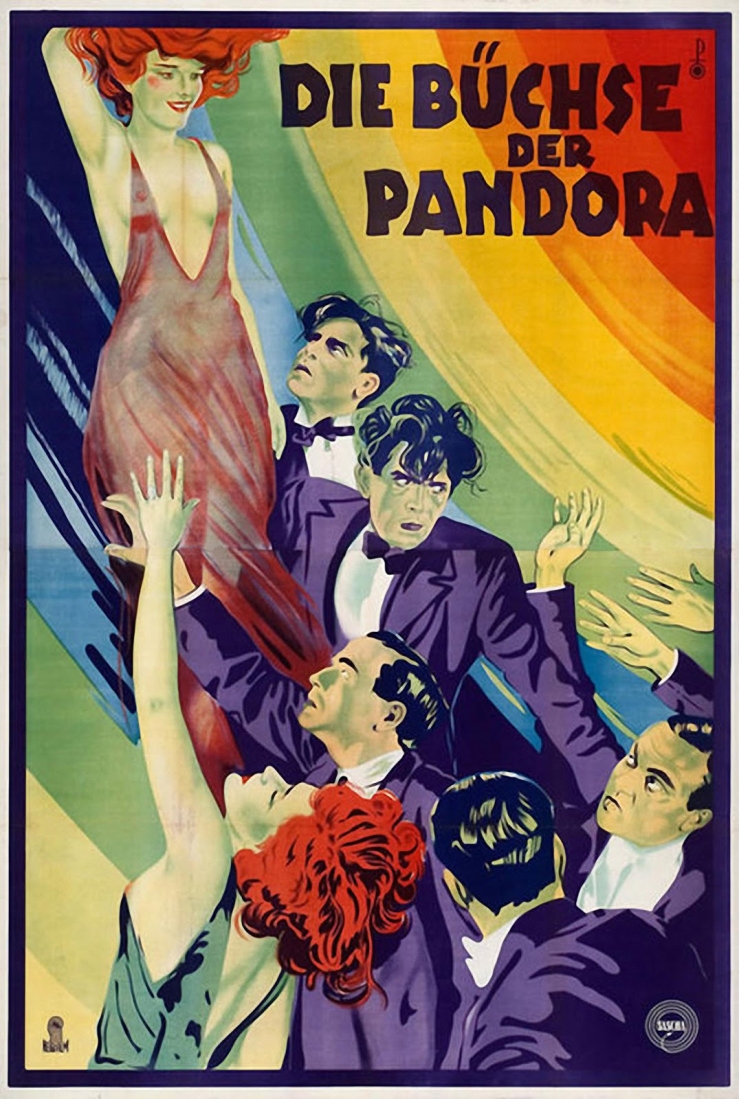

Though Pabst can often be overlooked in Weimar Cinema, he tackled social issues throughout his silents and talkies against the emerging New Objectivity. Adapted from Frank Wedekind’s plays Erdgeist (1895) and Pandora’s Box (1904), Wedekind’s narratives had been translated to cinema before with Leopold Jessner’s 1923 film, but Pandora’s Box became captivating through the energies of Pabst and Louise Brooks.

Greek mythology surrounding Pandora’s box and our relationship with evil may be diluted by time’s passage, the symbolism of Pandora reappropriated as a Danish jewellery company and the planet of Avatar (2009). But Lulu (Louise Brooks) explores this imagery well, embodied within Brooks’ cinematic image. As Brooks reflects in Lulu in Hollywood (1982), both Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl were “conducting an investigation into [Pabst’s] relations with women”, interested in the “flaming reality” of “sexual hate.” In his insightful 1983 essay Lulu and the Meter Man, Thomas Elsaesser argues Wedekind explored the femme fatale, and associations of transgression, violation and desire through the social milieu of class division. Pandora’s Box confronts not only bourgeois values but the male power curtailing the freedom Lulu seeks. Lulu’s relationship with newspaper publisher Ludwig Schön is formed of convenience of social standing, alongside his engagement to the daughter of the Minister of the Interior, Charlotte von Zarnikow, caught between the power of the press, sexuality and the political elite. Lulu is an alluring temptress to male authority; Rodrigo Quast seeks to exploit Lulu as part of his trapeze act, with Pabst’s fast editing adopting theatricality as she dons her outfit, stunning the theatrical audience and the viewer themselves. Like the carnival freakshow of Freaks (1932), Lulu has a sexual and romantic identity of her own, beyond the dehumanising gaze placed upon her by accepted societal values.

Schön’s double-edged threat – forcing Lulu, with his gun, to stage her own suicide, is itself coercive, taking agency from her death away from her, an impossible choice captured in immaculate detail by Günther Krampf. As Schön becomes a victim of the very suicide threat he levelled, Lulu’s judicious process is tragic: in the trial, she is faced with five years for manslaughter, despite her victimhood. Framed in close-up, Pabst captures the emotion and power of the desperation of her tears, faced with a jury who never knew. As Brooks reflects in Lulu in Hollywood, Pabst had no “stock emotional responses”, but sought actors to reach emotion “like life itself”. As the fire alarm is set off as a cunning escape, Pabst captures the unfolding chaos wonderfully. Lulu isn’t far away from the feminist heroine Angela de Marco in Married to the Mob (1988): facing presumed guilt against her husband’s murder in the bathtub by a bullet, we witness structures of power against her, through her avoidance of cops and her biased interview. As Elsaesser argues, Brooks’ Lulu is presented “practically without origin, or particular cultural associations”, with sexual desire part of a “more generalized structure of exchange”; sexuality lacks emotional engagement, with sexual acts and Reichsmark holding equal value. J. Hoberman writes that Pabst sought to create a fractured sense of eroticism, wanting “men in the cast to feel Brooks’s skin and have the actress get under theirs.”

In Lulu’s adventure in London, Pabst makes Lulu’s presence against male power most explicit. The mythology of Whitechapel and Jack the Ripper (Gustav Diessl) is buried within sensationalism of the press and tabloids and the police letter coining the killer’s name, enduring through the mystery of the ambiguity of his identity. The concept of the Ripper has a morality to it: a mutilator and murderer of prostitutes, attacking female sexuality in the slums and poverty of Nichols, Chapman, Stride, Eddowes and Kelly. Equally, the Ripper was formed against waves of Jewish and Irish immigration altering make-up and sentiment within 1890s London. The pervasiveness of representations border on the ridiculous: in film, the fictionalised killer of Hitchcock’s The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (1927), the time travelling pursuer of H.G. Wells in Time After Time (1979), a frequent foil to Sherlock Holmes across mediums, and in comics, the Gotham-based serial killer of Gotham by Gaslight (1991) and its giallo fan film Ripper (2016), the subject of Alan Moore’s From Hell (1989-98), an alter ego to Mr. Hyde in Thunderbolts #167 and the foe of IDW’s Doctor Who comic story Ripper’s Curse (2011). As Hutchinson notes, “sexually motivated murders”, or “Lustmord“, “filled newspapers and narratives in 1920s Germany”, from ‘The Butcher of Hanover’ to the Ripper’s role in Waxworks (1924) and Mack the Knife in The Threepenny Opera. The conflict between Lulu and the Ripper, her reflection and the Ripper’s knife – recalls Lulu’s previous use of the gun, returning to the paradigm between Lulu’s agency and victimhood. In the Christmas mistletoe, Pabst builds a remarkable sense of suspense, seeking the reveal of who moves first.

Louise Brooks will always be defined by her age: as the 21 year old actress in Pandora’s Box and Diary of a Lost Girl, the disjuncture of seeing her graceful ageing in her latter years in Lulu in Berlin (1984) and Kenneth Tynan’s rediscovery in his New Yorker piece The Girl in the Black Helmet. Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark’s eponymous 1991 song itself embraces the temporal disjuncture of “ghosts of long ago”:

And all the stars you kissed could never ease the pain

Still the grace remains, the face has changed

And you’re still the same

Having appeared in the avant-garde Denishawn troupe as a teenager and as a Broadway dancer, Brooks’ rising star emerged. As Hoberman notes, Pabst was inspired to cast Brooks after watching A Girl in Every Port (1928), attempting to borrow her from Paramount before she quit over a salary dispute. As German cinema fought against national boundaries, in a silent landscape supported by international coproductions and the universal language of the human face, American actress Louise Brooks could act alongside her German counterparts (with an Austrian director), a boundary that would continue to be stretched through the multilingual talkies that emerged, with a differently recorded version for each major market. Equally, as Siegfried Kracauer highlights in From Caligari to Hitler, the emergence of Kontingentfilme, or quota films, increased the distribution of foreign exports, with an increasing Americanization of Weimar cinema seeking to cater to American styles (1947:135).

Women in film are often underestimated, especially in melodrama, with “woman’s pictures” exploring women’s lives in deep, meaningful detail. With a handful of films, Brooks’ face joined the pantheons of women of early cinema, including Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich, decades before Monroe rose to fame, in part through her interwar flapper design. Kracauer notes critics found Pabst “fundamentally wrong” in adapting a “literary play”, with characters serving to “illustrate principles” (1947:148). Lulu is not just a character, but a symbol of female morality and sexuality. As Elsaesser argues, Lulu’s lack of family ties, social obligations, education and culture, and her freedom from guilt and conscience, assigns her as a “construct, not a sociological portrait”. Lulu is but an alluring, unreadable cinematic face of ambiguity and mystique, to read onto how we wish. Designer Gottlieb Hesch drew a sharp visual dichotomy through the contrast of Lulu’s costumes, between the purity of her white dresses and the sinful darkness of her black dresses, taken to full advantage through the film’s monochrome locations and cinematography. In Asphalt, we follow another woman on the other side of the law: Else moves through Berlin’s urban criminal landscape in her need to survive, frequently interacting with police, using sex appeal to seduce men and explore her femininity just as Lulu did the same year.

Pandora’s Box carries illicit beauty as we witness the dance between Lulu and Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), continuing their motions despite leering male onlookers, a rebuke to male power. Decades later, the lesbian sexuality of Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013), Carol (2015), The Handmaiden (2016), Thelma (2017) and the Black Mirror (2011-present) episode San Junipero remain rare delights as we deconstruct the fetishising and eroticising male gaze, the emaciated international form seeking to conceal these relationships. The boat’s gambling den becomes but another Weimar underworld, alongside the havens of Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and crime and kangaroo courts of M (1931), and, as Elsaesser writes, a “fictional metaphor for the economic chaos of the Weimar Republic”, but the underworld connotes a distinctly queer connotation, only emphasised by the West German-era underworlds of Fox and His Friends (1975) and the Isherwood based Weimar-era underworld of Cabaret (1972); Dietrich’s bisexuality made her but another element within this underworld. As Brooks reflects in Lulu in Hollywood, her residence at the Eden Hotel gave her a firsthand look at Weimar Berlin’s decadence, highlighting “girls in boots, advertising flagellation”, “agents pimped for the ladies”, sportsmen arranging “orgies” and the drag queens outside Eldorado, and the “feminine or collar-and-tie lesbians” at the Maly.

But Pandora’s Box is as much about Berlin as fleeing Berlin. With her passport, Lulu flees alongside her best friend, Alwa Schön (Francis Lederer), in far from ideal, squalid conditions. Like the foundational directors, seeking greater profits who fled to Hollywood, like F.W. Murnau, E.A. Dupont and Ernst Lubitsch, or fled anti-Semitism, like Fritz Lang, or Nazi-era directors like Douglas Sirk, or child refugees like Mike Nichols, without mentioning actors like Conrad Veidt, experienced dislocation from the country they were raised and born in amid developing tensions, adopting the United States as an inherited home. Dr. Mabuse der Spieler conveyed an international heist, but under the auspices of organised crime. Alwa and Lulu flee the country with urgency, emerging in Christmastime London that cannot escape Lulu’s inevitable fate, even amid the festive goodwill of Christmas puddings, window displays, gifts, snow and the marching Salvation Army. Posters, echoing the citywide search of M, warn of a criminal on the loose. Brooks was American, but in the following years, the Weimar cinema followed an inevitable collapse and migration. As Hutchinson argues, “geography carries crucial meaning”, highlighting Wedekind’s and Brooks’ own stays in London.

Günther Krampf’s immaculate visions have a tendency to be burned into cultural memory with his iconic image of the creeping shadow of Nosferatu (1922), but Krampf’s incredible eye is no stranger here either, illuminating in light the sinister London fog, prefiguring the film noir and its own femme fatales. Stephen Horne’s score provided a great compliment, integrating atmosphere, sounds of the train and fragments of Christmas carols within his piano performance. Like the greatest of live scores, Horne elevated the film he performed against to a place of beauty.