The 1980s are my decade. Which feels odd to say, given I was born in the late 90s. Politically, the period is interesting, juxtaposing commerce and capitalism and giving rise to neoliberalism (see: every Adam Curtis film ever), alongside nuclear paranoia and the legacies of Thatcherism and Reaganism. Comic books became darker, bringing interesting and meditative new takes to superheroes through V for Vendetta (1982-88), The Dark Knight Returns (1986), Watchmen (1986-7), Batman: Year One (1987) and The Sandman (1989-96). Music became what Donnie Darko (2001) would go on to celebrate. Meanwhile, the decade was populated with directors like Joe Dante, Oliver Stone and Walter Hill.

This list will never be complete: by my count, I watched 40 films from the decade over the course of the year. There’s simply too many to devote enough space to Blow Out (1981), The Last Starfighter (1984) or From Beyond (1986). But hopefully this will give a good overview of a decade whose cinema was populated by a diverse set of worlds.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains (1982), dir. Lou Adler

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains feels like how a model for how a Jem and the Holograms (2015) movie should be done. Rather than a surface level message around embracing individual identity and a modernised narrative of the social media popstar, the Fabulous Stains tells a story of teenage musicians from a genuine place, implicating the role of the media in promoting artists (and demonising its young followers) and its effects on the artists themselves. Where the punk aesthetic saw youth disenfranchisement and nuclear obliteration in Repo Man (1984), here we see how a cult emerges around an artist. Through the mantra of “never put out”, it grounds itself within the punk ideology of not selling out – but how tenable is that position? Incorporating faux news footage, Fabulous Stains settles more for ambivalence than anything else.

Lou Adler’s name may seem familiar – Adler has spent his entire career producing musical artists and launching Cheech & Chong as known artists. Adler knows the industry, so is able to use that experience to build an authentic narrative.

This type of empowering, feminist film feels particularly 80s; in The Legend of Billie Jean (1985), the commercialised, media cult of personality is again called into question, as Billie tries to defend herself against her rapist. In Brian K. Vaughan’s comic series Paper Girls (2016-present), the suburban young teenage narratives of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and more recently Stranger Things (2016) is subverted, applying those same coming-of-age struggles to female protagonists.

Starman (1984), dir. John Carpenter

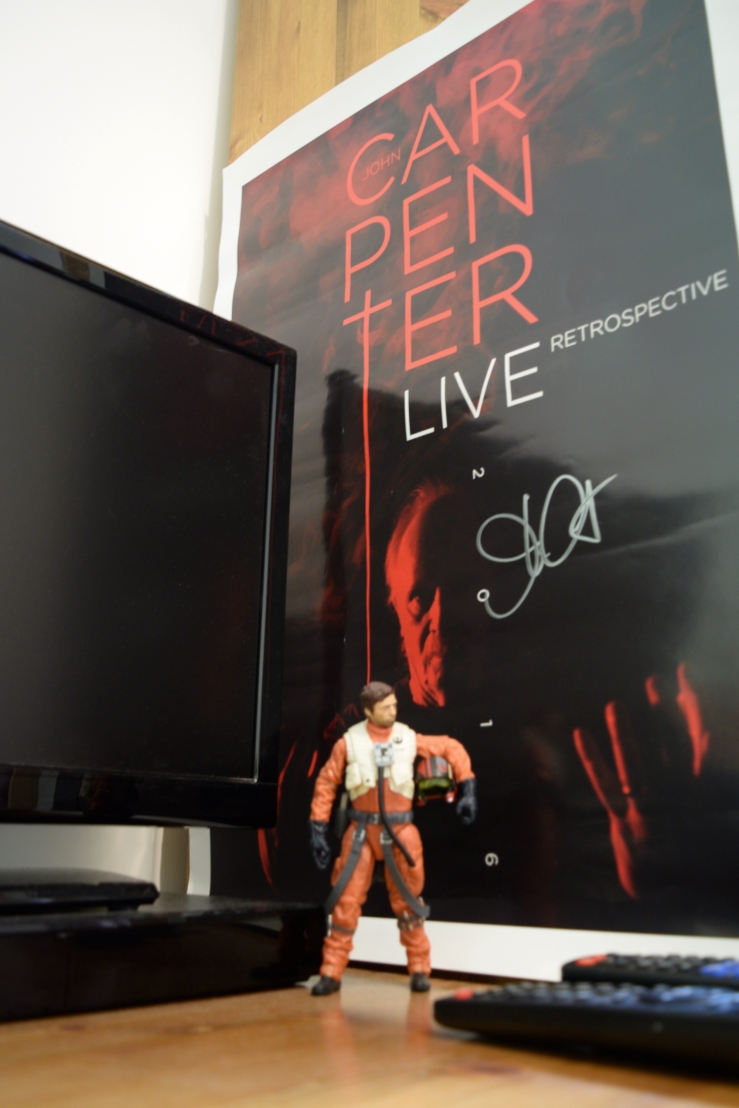

No other decade is as good at science fiction as the 1980s: from the acceptance of mortality in a Floridian retirement home in Cocoon (1985), to the nautical first contact of The Abyss (1989), to the apocalyptic, reality TV visions of The Running Man (1987). I have a soft spot for John Carpenter, and that’s not just because I spent the year blazing through his filmography with Big Trouble in Little China (1986) and Christine (1983), or saw him perform live in Manchester. Starman is far from one of Carpenter’s best efforts, and frequently transcends credibility, yet Starman is such a heartfelt story of a man from another world that it hardly matters.

The Starman’s appearance on Earth is Christ-like, visiting for a handful of days to bring peace until he must return home. Though he may seem creepy as he stalks Jenny and initiates a relationship with her in the form of her dead husband Scott, his only malice emerges from outside influences: government operatives, or a fight in the bar. In some ways, Starman is a road movie, as the Starman must travel from Wisconsin to Arizona in Jenny’s car before time runs out. Though Starman will never reach the cult appreciation levelled towards Escape from New York (1981) or They Live (1988), it still carries a special place in Carpenter’s filmography. Hopefully, with Indicator releasing Christine, Vampires (1998) and Ghosts of Mars (2001) from Sony’s catalogue on Blu-ray, we’ll be able to see a UK release of this very soon.

Blue Velvet (1986), dir. David Lynch

I’m unable to deal with the fact it took me five years to lose my David Lynch virginity. Back in 2011, when my friend Zach was introducing me to the Criterion Collection and other incredible films, I never thought to pick up the David Lynch DVD boxset I was eyeing up. I’ve still not watched Eraserhead (1977) or Mulholland Drive (2001), whilst I’ve still yet to complete my journey through Twin Peaks (1990-91) that I began in June amongst every other film or TV series, like Class (2016) or Black Mirror (2011-present) that is on my radar.

Rarely do I give a film 5 stars, unable to determine whether something is truly perfect, or the difference between 4.5 and 5. Yet Blue Velvet is as unquestionably perfect as a Stanley Kubrick film. Lynch stared into the frame and created a film with a true vision. As with the musical sequences within Twin Peaks, music takes on a performative female identity. Within the noir genre, aided by the presence of Kyle MacLachlan, Lynch creates a gripping portrait of sexual power, dominance, masculinity and femininity, with shades of some of his later works.

Miracle Mile (1988), dir. Steve De Jarnatt

Miracle Mile opens in a nighttime coffee shop in Los Angeles; it ends in a helicopter. Over the course of the film, Harry tries to outrun the inevitable, moving between the Mutual Life Benefit Building and gymnasiums, rescuing family in the process. Miracle Mile‘s nihilistic approach to the end of the world seems to have shades of how the Death Star’s power is treated in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016). Yet it fits with an entire genre of 1980s cinematic nuclear apocalypses, from The Day After (1983), Threads (1984) to When the Wind Blows (1988).

Yet Miracle Mile embeds lightness within its darkness: Night of the Comet (1984) may have dealt with the death of almost everybody in Los Angeles, but it still had Girls Just Want to Have Fun. Here, we open in a diner defined by caricatures, from drunks to clerks to drag queens; later, we meet body builders, or old women going on dates. Unlike the soul-crushing Threads, the strength of Miracle Mile is how it oscillates between these two tones, only amplifying the power of the desperation of the film’s ending.

For All Mankind (1989), dir. Al Reinert

Brian Eno’s music can help make any film moving and incredible, from Rachel’s struggle with cancer in Me and Earl and the Dying Girl (2015) to Todd Haynes‘ portrait of 1970s London in Velvet Goldmine (1998). Here, Eno’s music almost becomes a transcendental experience, as beautifully linked to the visuals as Philip Glass’ was in Koyaanisqatsi (1984). Rather than leave archival footage of the moon landings in a vault, ready to be used in extract form in every TV special or documentary, alongside assorted talking heads of variable value, allows this footage to be played in full, in the best quality available. For All Mankind is one of very few films which can truly attest to being largely filmed in outer space.

Space may be just as inspiring within fictional narratives, but For All Mankind is something special. We never doubt the science, or the dubious CGI, or if this is what a spacecraft is actually like. Yet it still feels like science fiction, never our reality. Though many voices have tried to retell their experiences of the Apollo missions, here their voices become a collective – a collective experiences of multiple missions – told within one story. For All Mankind never reaches the narrative suspense of what one expects from a fiction film or a documentary – but it remains a spectacle, that needs to be seen. Not in some 480p YouTube version – but on the Criterion or MOC Blu-ray. Looking out at the universe, this film deserves to be seen in all its glory.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape (1989), dir. Steven Soderbergh

Sex, Lies, and Videotape makes for uncomfortable viewing. But it’s meant to. Often, there’s a recent tendency with films examining the emotional impact of sexuality to rely upon explicit sex scenes, whether simulated or real. Think of recent examples like Shortbus (2006), Nymphomaniac (2013) or Love (2015), even outside of Fifty Shades of Grey (2015). These films seem split in critical opinion: are they porn, or are they art? I’ve had an uncomfortable relationship with my own sexuality. I’ve made a lot of mistakes and bad decisions, something I’ve really had to confront over the past year, embracing my asexuality.

Sex, Lies, and Videotape is uncomfortable, yet it is uncomfortable in its characters and scenarios, from Graham’s VHS library to Ann’s actions within the film, instead resorting to confessional style monologues; never does it use sex itself to make the viewer uncomfortable. It is not about the sex act itself – but the impact of it. Videotape carries a universality around its taboo – whether one is poly, ace, mono, straight, queer, everyone has their own relationship to sexuality. Soderbergh deconstructs sexuality – just as he does with masculinity in Magic Mike (2012).

The venue seems to have received a wide amount of flack on social media, with numerous ticket holders complaining about being unable to see anything, or hear much at all either. A few days later, the Facebook page was completely down.

The venue seems to have received a wide amount of flack on social media, with numerous ticket holders complaining about being unable to see anything, or hear much at all either. A few days later, the Facebook page was completely down.

You must be logged in to post a comment.