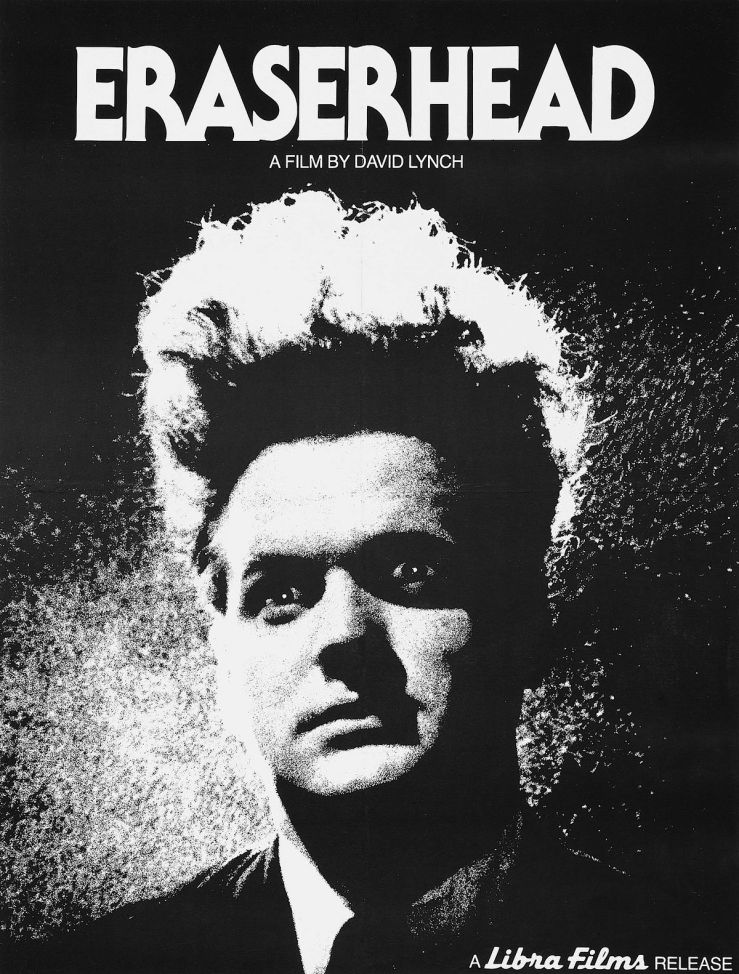

The highlight of the Flatpack Film Festival was something I’d anticipated for weeks: a sold out screening of David Lynch’s first feature Eraserhead, presented with a live score by French indie band Cercueil. Cercueil’s score pervades the film with unease, heightening the surreal atmosphere. Sparse dialogue becomes distorted, echoing through as though in a tunnel. Cercueil’s score is no substitute, but a welcome alternative.

1977 was an important year in cinema history: Star Wars redefined what the blockbuster and science fiction fantasy could be, drawing massive crowds. Close Encounters of the Third Kind proved Spielberg wasn’t going away, inspiring a generation to watch the skies. But 1977 was also the year David Lynch was unleashed upon the world, catapulted through midnight screenings outside the studio system. Eraserhead’s development was long, emerging from a grant during Lynch’s period at the AFI’s Center for Advanced Film Studies.

Lynch had been working on a 45-page script for a film called Gardenback, based upon one of his paintings. Recalling in Eraserhead Stories (2001), Lynch didn’t remember writing a script, but developed a 21-page outline. Lynch was afforded space and time to develop, living and working from stables in Beverley Hills that were mostly his. The crew worked other jobs: assistant director Catherine E Coulson worked a day job at BBQ Heaven; Lynch delivered papers at night for the Wall Street Journal.

Lynch’s name might be best at home with experimental artists that defined underground cinema through the mid-to-late 20th century: Kenneth Anger’s occultism and queerness; Stan Brakhage’s abstract shapes; Derek Jarman’s punk aesthetics applied to cinema. Lynch’s filmography may bend rules of narrative cinema to Lynch’s own aesthetic, but largely holds onto its generic conceits: engaging protagonists, narrative goals, mysteries. Plot is never Eraserhead’s priority, going far deeper into the depths of Lynch’s mind, into the surrealism of experimental cinema. Eraserhead is identifiably Lynch. Lynch explores female sexuality, bathed in pools; the mother making moves on Henry Spencer (Jack Nance), although perhaps not to the extremes of Blue Velvet (1986), Mulholland Drive (2001) or Fire Walk with Me (1992). The carpet is identical to the carpet in the Red Room in Twin Peaks (1990-91, 2017), cast in stark monochrome. The Lady in the Radiator, emerging from a picture Lynch scribbled in the food room, sings In Heaven in haunting, emotive repetition.

In Heaven

Everything is fine

You got your good thing

And I’ve got mine

Over 6 years of production, Lynch followed a wave of creativity. As he tells Chris Rodley, Lynch developed an idea for an educational series with Coulson entitled I’ll Test My Log with Every Branch of Knowledge, about a young mother who lost her woodsman husband in a forest fire and carries her log everywhere, that eventually manifested as the Log Lady in Twin Peaks.

Lynch’s use of monochrome is superb, showing dedication to the image thanks to cinematographers Herb Cardwell and Frederick Elmes. Monochrome might be born of necessity from economic limitations, but has aesthetic potential both in adding dramatic weight and surrealism. When done wrong, monochrome can seem flat, but monochrome can elevate films like La haine (1995) and Nebraska (2013), evoking an entire mood, beyond the evocations of historical contexts in Schindler’s List (1993) and Ed Wood (1993). Lynch wanted to capture a mood, filming at night without external lights or sounds, creating a descent into the subconscious.

Though Eraserhead is surrealist, its power doesn’t lie within abstraction, but grounded within the real. Eraserhead’s concerns are human: tending after an ailing parent, raising a son, resolving family conflict, the relatable circumstances of Mary X (Charlotte Stewart) bringing her boyfriend home to her awkward yet interested family, a ritual all likely go through. Lynch had explored conflicted parental relationships in his experimental short The Grandmother (1970), but Eraserhead goes deeper. The industrial landscapes were drawn from Lynch’s own time in a decaying Philadelphia, forming “a world between a factory and a factory neighborhood” of “little torments” that is “neither here nor there”.

Though never autobiographical, Lynch drew upon his experiences, both in his deteriorating relationship with his wife Peggy and daughter Jennifer, who spent time on set. As Joel Blackledge writes, Lynch was a “reluctant father”: Jennifer was born with club feet, whilst Spencer’s “dark suit and gravity-defying hair” evokes Lynch’s “trademark look”.

Eraserhead moves into our own consciousness and bodies. Consciousness is an absurdity: minds within an embodied vessel of flesh and bone. Lynch questions our existence and its unreality, manifesting latent fears and anxieties within cinematic form. What makes us us? The head, beyond a vessel for consciousness, is an easy subject for experimental cinema. In A Trip to the Moon (1902), Méliès’ anthropomorphised moon gazes upon us; in Dimensions of Dialogue (1982), human faces meld into each other. Lynch’s visual effects are incredible, creating a design of an alien baby that stuns to this day. Lynch relies upon shock: a chicken dances; creatures stomped on; an eraser’s head is sharpened.

As he tells in Eraserhead Stories, Lynch found resources for the film from wherever he could, raiding a closed down studio for wire, nails and backdrops. Lynch contacted a veterinarian to acquire a dead cat that Lynch placed within a jar and dissected, watching the colour drain away from its internal organs; the cat never appears in the film in a recognisable form. Spencer’s suit and shoes were acquired from Goodwill; Coulson cut his hair. Eraserhead was completed and found distribution outside the festival circuit thanks to the monetary investments and finishing money from Jack and Mary Fisk and Sissy Spacek; its legacy continues to be felt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.